The Humor Code, by Peter McGraw and Joel Warner

This is going to run a bit long. Short version? If you're a humorist of any stripe, buy this book.

Long version...

I present lectures on how to write humor from time to time at conventions, and I've guest lectured on the subject several times now in Brandon Sanderson's writing class at Brigham Young University.

I present lectures on how to write humor from time to time at conventions, and I've guest lectured on the subject several times now in Brandon Sanderson's writing class at Brigham Young University. This is not because I'm an expert. I'm just a student of humor. I've studied lots of theories about why we laugh at things, and attempted to apply them. I've drilled down a bit into what happens to us when we laugh at things, and how weird that involuntary metabolic response really is. Oh, and I've spent about fifteen years trying to make other people laugh at things I've thought up.

The Humor Code, by Peter McGraw and Joel Warner seemed at first like a good addition to my repertoire. As it happens, it is now a container for the entire repertoire, and solid evidence that you should be listening to Peter McGraw speak instead of listening to me (you can still read my comic, though.)

Humorists look at theories of humor with skepticism, because they suspect that the theorist is looking for a joke formula that will always work, an "easy" button for a career in stand-up or in the funny papers webs. A practicing humorist knows that if there were such a thing, some humorist would have already stumbled across it, but they haven't, and making jokes work is difficult.

The Humor Code doesn't make it much easier, but it does explain why it's difficult.

I used the term "formula" up there. That suggests chemistry. Here, then is a pretty good metaphor: The Humor Code is to humor as the classical model of the atom is to chemistry. That classical model explained why all of the different chemical formulae worked the way they did, and it also explained why there would never be a formula that would turn lead into gold.

The book itself is fun to read. It's anecdotal, but each anecdote is used as a framework to discuss hard, empirical research, and to posit possible challenges to the results. The reference section in the back comprises roughly 20% of the book, but the preceding 80% of the book tells a great story. In short, it is entertaining, educational, and yes, there is real science in there.

Up until I read The Humor Code, the best model I'd seen was a line from Larry Niven's Ringworld, in which one of the characters says " humor is associated with an interrupted defense mechanism." I've long thought that this could explain anything from slapstick to puns, from ribald humor to the revelatory, cognitive stuff. Anything that puts our hackles up is a candidate for "funny."

The actual model is far more elegant.

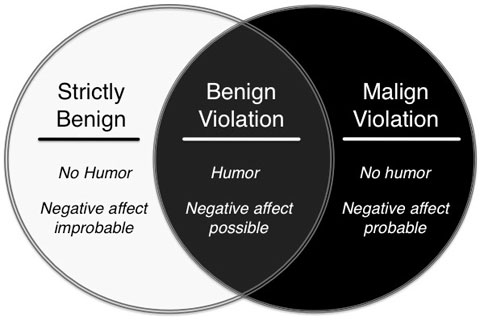

Image courtesy www.petermcgraw.org

If a thing is simultaneously benign (it's not going to hurt the listener) while violating something (rules, personal space, good taste) then it's funny to the listener. But different people have different areas of overlap, so the professional humorist must map the "Benign" and "Violation" domains shared by the audience in order to come up with jokes that will work. Complicating matters, those domains can move during the course of a routine. This is why delivery is so critical, and why I will often spend far more time refining the panels that lead up to the punchline than I spend refining the punchline itself.

My interpretation of that diagram is no substitute for reading the book, and I suspect that reading the book is no substitute for reviewing Peter McGraw's research and visiting with the team at the Humor Research Laboratory ( HuRL) in Boulder, Colorado. I'm too busy for a road trip, but the first part? Well worth the time and the money.

If you are interested in making funny things, or in making non-funny things into funny things, The Humor Code is worth your time and money too.